Three Defensive Encounter Mistakes to Eliminate Now

Data from the Centers for Disease Control demonstrates that approximately 2.2 million times per year, peaceful civilians in the United States retrieve, present, or otherwise use a gun to resolve a violent encounter or prevent violence. That’s six times the rate at which criminal actors introduce a gun into their work. The vast majority of these incidents end peaceably and are never reported to police.

The success of regular people in using guns as part of a security plan is obvious. Yet too many times, encounters end in victimization. Here are three key areas where everyday people sometimes fail to exercise good judgment; failures that can lead to the necessity for violence on their part, or, once the decision is made to fight, failures that can end in tragedy.

1. Failure to avoid or leave a high-risk situation early on.

Normalcy bias is the pop psychology term for the tendency to not regard warning signs of danger for what they are, as well as for not taking action when it’s clear that complacency can lead to doom. Be aware of the tendency toward normalcy bias within yourself as well as within groups. Cultural conditioning tells us not to judge others unfairly. That doesn’t have to translate into endangering yourself in an effort to be non-judgmental

Endless tolerance in the face of warning signs can be deadly,

An earlier post on this blog addresses pre-attack indicators for typical street crime and acquaintance conflicts. Most of the time, violence is signaled before it occurs. Whether it’s the person at the store counter keeping her hands in her pockets when most people would be ready with credit card or cash in hand, or the first time a new sweetheart makes a not-funny wisecrack about how hitting is necessary to keep a relationship strong, it is time to be vigilant and formulate and escape plan if not an outright withdrawal from the situation then and there.

Groups of people can collectively peer-pressure each other into normalcy bias. Fear of appearing intolerant stops people who, acting alone or with family, wouldn’t hesitate to immediately avoid or address out-of-place behavior. The behaviors your workplace, community center, or church may accept in the name of tolerance could put you and others at risk. Thanks to the shuttering of effective care programs for mentally ill people and the increasing failures of the American justice system, there are greater numbers of people walking around in virtually every part of the country who have a history of violent crime or addiction—and are likely to offend again to support their lifestyle.

2. Failure to distinguish between brandishing versus a show of force, legally speaking.

A common myth among the concealed carry set is that the gun is never to be drawn unless the person wearing it is positive they’re going to fire. I carried this fallacy around in my own mind years ago, until good training and life experience helped me understand otherwise.

Brandishing a deadly weapon, an act that may go by other names in criminal code depending on jurisdiction, is a wanton act that should be penalized severely. Brandishing is often associated with road rage. One driver cuts another off, and instead of ignoring the rude behavior, the cut-off driver catches up to the errant one, rolls the window down, and gestures with pistol in hand, usually yelling some unintelligible, four-letter word-peppered epitaphs at the same time. Brandishing invites a fight and has no place in the civilized existence of the concealed carrier.

A show of force is both a civilized and life-saving behavior, for both the lawfully armed person and the would-be attacker.

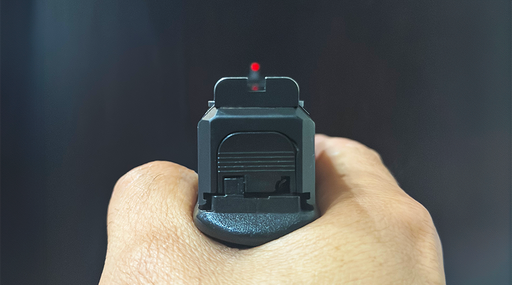

What is a show of force? It’s signaling to a would-be attacker that you are armed and will not hesitate to stop their actions if they don’t immediately stop themselves. Most often, that means a gun is drawn and is in a so-called ready position, generally not pointing directly at the assailant’s center mass but in a position where it rapidly could be.

People generally overestimate the time they’ll have to draw and possibly fire their gun. At the same time, people underestimate the time and distance in which a blade, bludgeoning tool, or fist can reach them. The guideline and training tool by respectable civilian and law enforcement academies that bears the name of its originator, Dennis Tueller, tells us that 21 feet—the size of most living rooms-- is a good minimum distance that an undeterred, fast-moving attack can go from being “over there” to making a deadly strike—in about 1.5 seconds. Most concealed carriers haven’t mastered drawing their gun in less than 1.5 seconds, let alone making at least one accurate hit in that time.

The math shows us that having the gun out in a ready position may be the only life-saving option if an attack is likely. It’s not only life-saving for the armed citizen, it’s often life-saving for the would-be criminal as well—or at least his/her accomplices, who almost always flee when the first shot is fired by a would-be victim. It’s humane, after all, to give the criminal a clear choice—leave me alone or pay the price of attempting to hurt me. If you think you’ll start to draw after the attack starts, you will probably lose.

3. Allowing bad gear or poor handling to defeat a good person.

“Don’t let your equipment defeat you” is the favorite saying of one of my gun-training mentors, Terry Nelson. As an instructor as well as a longtime concealed carrier, I’ve seen thousands of examples of poorly designed holsters, inefficient carry methods, and clumsy, slow, sometimes dangerous gun-drawing techniques.

Eschew any desire for coolness or emotional attachments related to your gun and gear.

Pick the equipment you carry based on reliability and accessibility. Does the gun go “bang” each and every time you attempt to fire? If not, if any part of that is your fault, fix it! If any part is the gun’s fault, fix or replace the gun. Does your carry position and holster allow you to access the gun with effort that would not be noticed across the room? While any gun on your person is better than none, not all carry positions are equal. If drawing your gun requires bending over or looking down, understand in those moments you are at increased risk of not only assault but of having the gun forcibly taken while you’re in a compromised position.

A thriving segment of the gun industry is the accessories department. I have lost track of the number of modified Glocks alone that I’ve seen that have been messed with so much, mechanically speaking, that they do not cycle properly. Don’t fall for the notion that more modifications or add-ons are better. With a few exceptions, it’s the opposite.

By the same token, the best concealment setup requires practice on getting the gun out of the holster. Spend some time in your various seasonal outfits in front of the dresser or bathroom mirror---with magazines and ammo in another room—practicing your draw until you can’t get it wrong! Get good training from a professional, too. I’m often amazed at the easily resolved, yet egregious safety errors people make drawing and re-holstering from concealment. From muzzling the brachial artery of their own support hand, to muzzling everyone in what would be a public area for 90 degrees when drawing from a cross-draw position, don’t let your carry method set you up for tragedy or failing to win the fight for life.

The honest self-assessment

Think over the times of your life when you may have not acted or acted too late due to feeling lazy or feeling peer pressure to keep the status quo. Think about the typical distances at which you might encounter a threat in daily life---the distance of your workplace hallway or working areas; your favorite table in the coffee shop to the door, etc. Think about what it would take to get your feet moving to escape or fight back in those places. What stumbling blocks do you find? What are you doing to resolve them? Range practice is necessary to stay competent, but avoiding the common mistakes named here takes some mental practice as well. Put your reps in, on a regular basis.

Eve Flanigan is a defensive shooting and concealed carry instructor living in the American Southwest. Today she works full time as an instructor and writer in the gun industry. Flanigan loves helping new and old shooters alike to develop the skills needed to keep themselves and their loved ones safe.

Leave a comment